IVDD can be a pain in the neck! But what is Intervertebral Disc Disease, exactly?

I’m willing to bet that all of you reading this post have seen an adorable video of a Dachshund, French Bulldog, or Corgi in a wheelchair. Many dogs of many different breeds need wheelchairs for many different reasons, and this post discusses one of the most common causes of paralysis in dogs. While a diagnosis of IVDD can be incredibly frightening, there is profound hope and many effective pathways to improved mobility and quality of life.

What is Intervertebral Disc Disease (IVDD)? A "Slipped Disc" Explained

Intervertebral Disc Disease (IVDD) is a degenerative disease in which the outermost structures of the disc—the part that’s right up against the spinal cord—break down over time, allowing the inner portion of the disc to rupture out of its designated space between the vertebrae, and apply pressure to the spinal cord. IVDD is most commonly seen in short-legged, long-backed breeds such as Dachshunds and Corgis, but can be seen in any breed of dog, and sometimes in cats. Other dogs that are prone to spinal malformations, such as French Bulldogs and Pugs, also suffer frequently from episodes of IVDD.

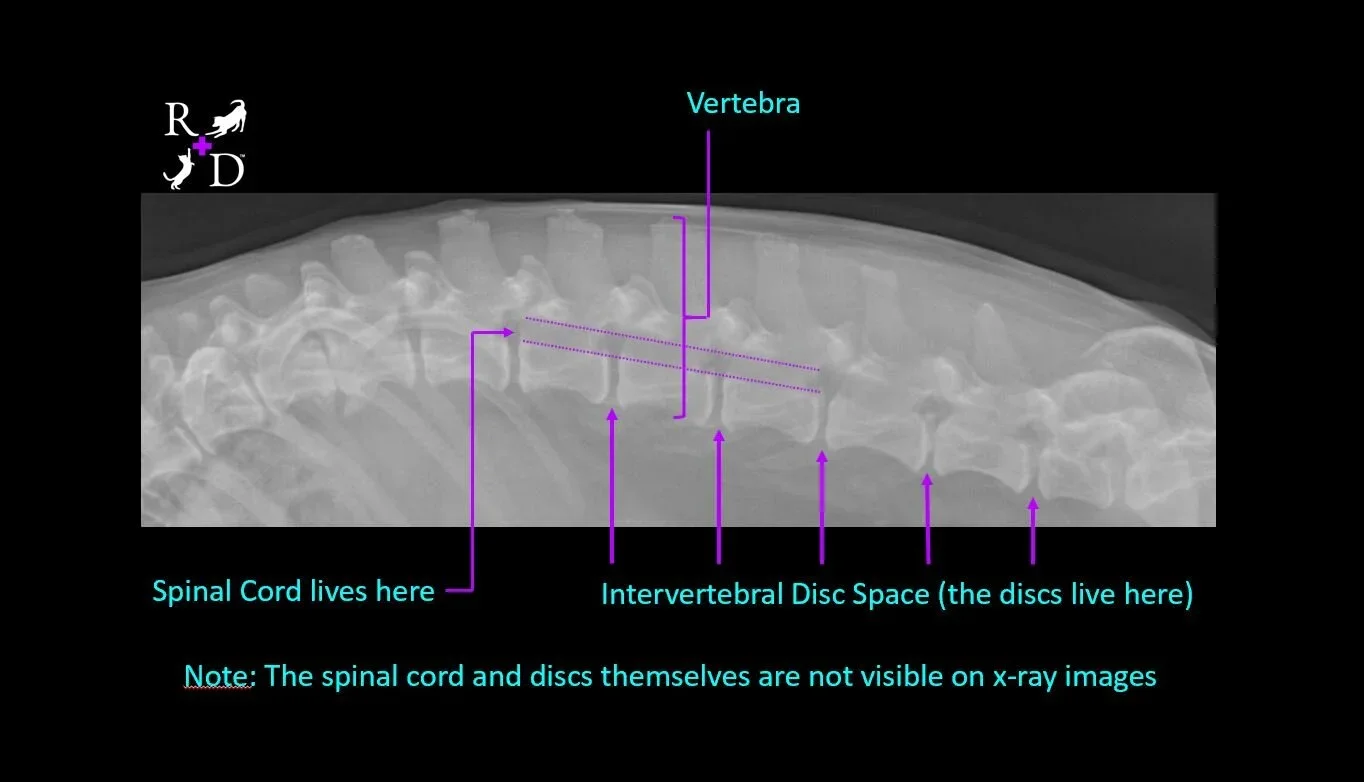

In the x-ray image (radiograph) shown above, you can see the vertebrae, which are the bones that make up the spine. Between those vertebrae is a blank space within which lives the intervertebral disc, which provides a cushion between the bones that allows for spinal flexibility and ease of movement. Coursing through the vertebrae, in a canal just above the disc spaces, we find the spinal cord.

How is Intervertebral Disc Disease Diagnosed?

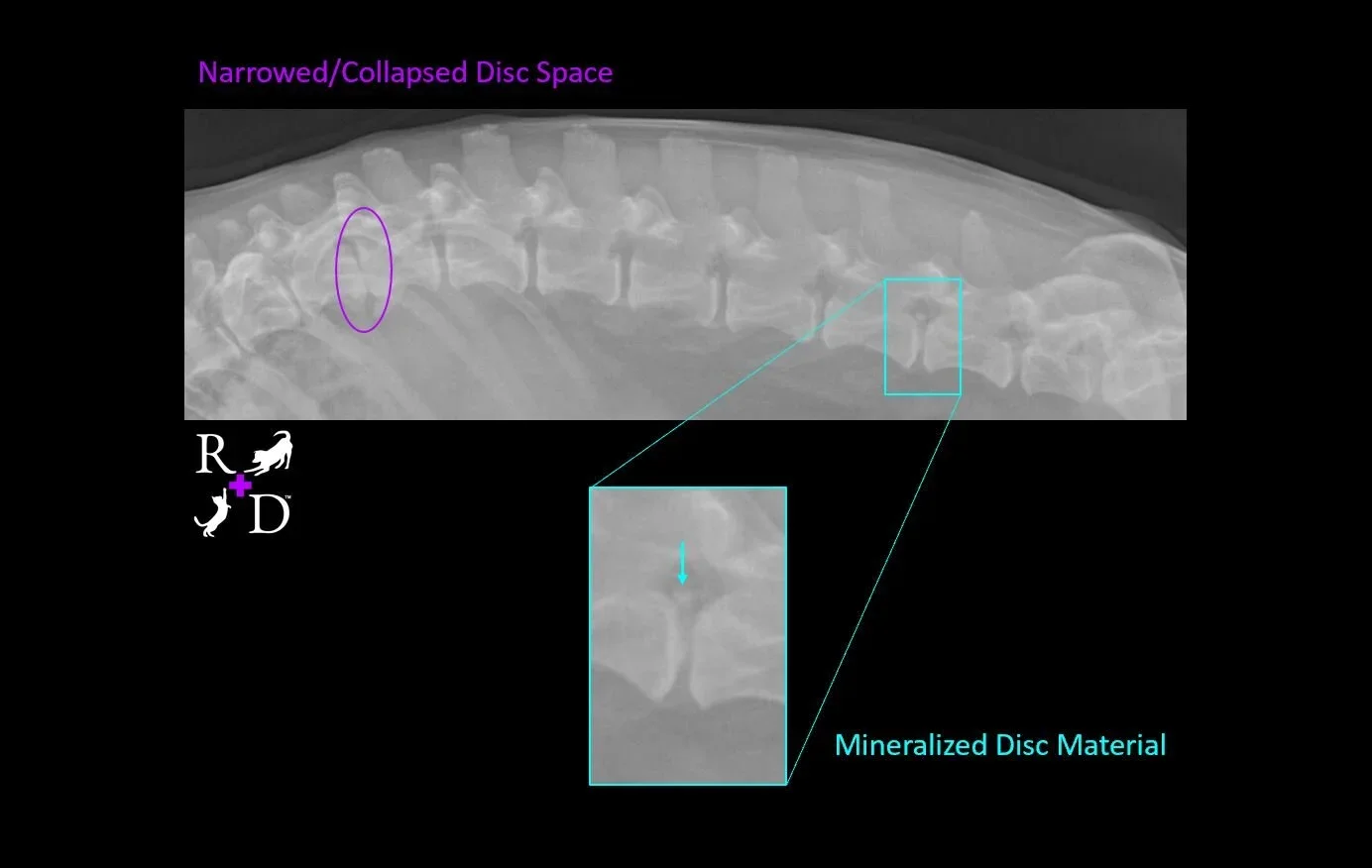

The actual disc itself is not visible on regular x-ray images, nor is the spinal cord, and in order to visualize these structures, advanced imaging such as an MRI is often necessary. But even though we can’t see the discs and spinal cord, we can often find clues on x-ray images that IVDD could be a problem for that patient. In the image shown below of my own dog’s spine (Ralphie), he has evidence of IVDD visible in two separate locations. In his thoracic spine, where the vertebrae have ribs attached (seen on the left side of the image in purple), we can see that one of his disc spaces appears quite narrow compared to the others around it. When the disc material ruptures out, it’s like a tube of toothpaste squeezing out its contents. As more of the toothpaste inside comes out, the tube becomes smaller and takes up less space. Over time, if surgery is not performed to remove that disc material from around the spinal cord, the extruded disc gets dehydrated and starts to scar down. Part of that scarring process results in deposits of minerals (mostly calcium), which does show up on x-ray images, and looks similar to bone. You can also see this process happening in Ralphie’s lumbar spine (the right side of the image in teal). Since this scarring process happens over time, we know that his lumbar disc extrusion happened long before this x-ray image was made.

As I said above, though, to get a definitive diagnosis, we must obtain an image of the spinal cord itself and evaluate it for compression. This is done by advanced imaging, such as with an MRI or a CT scan. In patients who are headed to surgery, this imaging is critical to:

Confirm the diagnosis—nobody wants to go to surgery without being pretty sure it’s the right thing to do, and

Guide surgical planning by helping the surgeon ensure they are planning their surgical approach at the correct disc space.

Patients who don’t go to surgery rarely have this advanced imaging performed, and we veterinarians base the patient’s diagnosis on clinical signs, and the little hints we might be able to pick up on with x-ray images as discussed above.

What are the Signs of IVDD? Recognizing Your Pet's Signals

I have personally seen the whole gamut of clinical signs in cases of IVDD, ranging from mild, intermittent signs of pain all the way up to complete paralysis. The severity of signs we see depends upon the location in the spine where the problem disc is found, how much of the disc material is putting pressure on the spine, and over what length of time the process has been going on. For the most part, though, severity of clinical signs worsens with more aggressive spinal cord compression.

Mild to Moderate Pain: Subtle Discomfort

If just a little bit of the disc has ruptured and it is applying only light pressure to the spinal cord, very likely the patient will experience mild to moderate pain, often at seemingly random times. Early on in this disease process, some people describe that their pets will be walking or playing normally, then will suddenly yelp as if in pain, act uncomfortable for a few minutes, then return to normal. As more disc material applies more pressure on the spinal cord, we will start to see more severe signs of pain. Often these patients are hiding or trembling, arching their backs, and walking gingerly or with a distinct limp. It is very common for these patients to be really tense in their abdomen, too (this is compensatory--they tense their abdomen to avoid moving their spine), and it’s common for people to mistakenly attribute these signs to constipation or a gastrointestinal problem.

Neurological Deficits: Changes in Movement & Coordination

As still more disc material is extruded, it results in compression of the spinal cord that is severe enough to interrupt the transmission of nerve signals, causing nervous system abnormalities. The outermost portion of the spinal cord carries the fibers that communicate to the brain where the body is in space, called proprioception. This means that the first neurological deficit we’ll see is ataxia (a drunken, uncoordinated appearance to the pet’s movement), often accompanied by knuckling of the feet.

Loss of Voluntary Movement & Sensation: Paralysis & Urgency

Deeper in the spinal cord we find fibers that control a patient’s ability to voluntarily move their bodies. When these fibers get compressed, patients lose the ability to walk, but often still have some sensation in those legs. Essentially, the brain says "step forward with your back right leg" and the leg doesn't get the memo, but the leg can still send signals back to the brain about how it's feeling. Depending on where in the spine the injury occurred, patients may also lose their ability to urinate and/or pass feces on their own—the loss of the ability to urinate is ALWAYS considered a medical emergency that requires immediate veterinary attention. In the very middle of the spinal cord run the fibers that detect deep pain, meaning the ability to feel a very painful stimulus. When these fibers are compressed, a patient has lost all neurological function and they are considered paralyzed. You may see this written in Veterinarian’s notes as “Deep Pain Negative.”

Every patient is different in how they show signs of IVDD. Some patients show mild, intermittent signs that never progress, as has been the case with Ralphie. Some patients live with mild, intermittent signs for some time, then suddenly develop more severe clinical signs. Some patients experience this very acutely and, despite no history of medical problems, and no history of trauma, suddenly lose their ability to walk.

How is Intervertebral Disc Disease (IVDD) Treated? Pathways to Recovery

Many patients with IVDD undergo an aggressive spinal surgery in which part of the vertebra adjacent to the extruded disc is removed, and a tiny spoon-like device is used to remove as much of the disc material from around the spinal cord as possible.

In Veterinary Medicine, it used to be that if a patient couldn’t go to surgery, euthanasia was the only humane option for that pet. Thankfully for many of Ruff Day Vet + Pet Gym’s patients (and their humans who love them so much), and other IVDD patients around the world who have been treated by rehabilitation veterinarians, that is no longer the case!

Whether a patient with IVDD goes to surgery or not, I strongly believe that all cases of IVDD should be treated by a veterinarian or physical therapist trained and certified in canine rehabilitation, as well as a veterinarian trained in acupuncture. Through Ruff Day Vet, I do both!

Comprehensive Non-Surgical Management: Our Integrative Approach

At Ruff Day Vet, we are uniquely equipped to provide comprehensive non-surgical management for IVDD, offering profound hope and tangible pathways to recovery. Our approach centers on supporting the spinal cord's healing, reducing inflammation, managing pain, and rebuilding lost function. We achieve this through a personalized blend of therapies:

Rehabilitation Therapy: Our Pet Gym focuses on customized exercise regimens, neuromuscular re-education (rebuilding communication between brain and muscles), and building core strength and stability to support the spine.

Acupuncture & Eastern Medicine: Acupuncture and electroacupuncture can effectively reduce pain and inflammation, stimulate nerve healing, and improve neurological function.

Advanced Therapies: Modalities like Therapeutic Laser and Shockwave Therapy accelerate tissue repair, reduce swelling, and promote cellular healing in affected spinal areas.

Mobility Devices & Support: For pets with significant weakness or paralysis, we offer expert guidance and fitting for mobility aids like slings, braces, and wheelchairs to support independence and dignity.

Post-Surgical Rehabilitation: Maximizing Recovery Potential

For patients who do undergo IVDD surgery, rehabilitation is not just beneficial—it's often critical for maximizing recovery potential. Our targeted rehabilitation programs work in tandem with surgical recovery, helping to:

Accelerate healing of surgical sites.

Reduce post-operative pain and swelling.

Prevent muscle atrophy and stiffness.

Restore lost function and coordination more quickly.

Rebuild strength and stability to support the surgical repair.

By combining surgical intervention with dedicated rehabilitation, we strive for the most complete and rapid recovery possible, helping your pet regain their confidence and mobility.

About the Author: Dr. Heather Misener, DVM

This article was crafted by Dr. Heather Misener, DVM, CCRT, CVAT, CVNN – Co-Founder, Medical Director, and Veterinarian at Ruff Day Vet. With extensive certifications in Canine Rehabilitation Therapy (CCRT), Veterinary Acupuncture (CVAT), and Veterinary Natural Nutrition (CVNN), Dr. Heather brings a profound dedication to integrative care (a holistic approach blending conventional medicine with complementary therapies). Her philosophy centers on empowering pet owners through clear education and fostering a fear-free environment (where pets are comfortable and willing participants in their care), guiding cherished companions toward lasting comfort and optimal vitality.

Ready to Explore Hope for IVDD?

If your pet has been diagnosed with IVDD, or you suspect spinal pain, know that there are effective paths to comfort and restored mobility. We invite you to explore a comprehensive, integrative approach.